April winds bring a curious alchemy to our dusty hills. The magic is this: dirt, our very own loess, is transformed into silver and gold. And the treasure chest of Paradise brims with the golden rays of Arrowleaf Balsamroot flowers and the silver sheen of their leaves. In our fields gone feral, on our hills un-bruised by human hands, in our parks, and upon our ridge tops, gold and silver tumble down.

More sophisticated than pure gold and far superior to actual silver, these wild flowers outshine those inedible, domesticated minerals of arbitrary value. This gold and silver can feed us, without the middlemen. From root to seed and all parts in between, these holy, shining fortunes sustain soul and body both.

Unless you have a sunshine allergy or severe agoraphobia, I am confidant that on some April day you have seen a hoard of yellow "sunflowers" around. And it was surely the gorgeous bounty of Arrowleaf Balsamroot (heretofore referred to as AB).

AB, of the Aster family, is nearly identical cousins with the Common Sunflower, reflected by layman's terms: Spring Sunflower and Wild Sunflower (Food Plants of the Interior First People by Nancy J. Turner). You can deduce from these common names that AB's flowers are sun-oidal with golden rays extending from a round gold center.

The leaves, as the name more than suggests, are arrow shaped, growing up to two feet long. A sheen of white hairs tones down their green to a trendy silver/green hue. These leaves clump together and produce a bevy of one-flowered stalks from 8" to 30" tall. The official sunflower sprouts many heads per stalk, but AB believes that flowering involves only one flower and one stalk, together for the rest of their lives.

The roots, which apparently smell of balsam, as the name in both scientific Greek Balsmorhiza sagittata and plain English indicates, are rich in carbs and fiber both (www.usask.ca "Rangeland Egosystems and Plants). Before miners dug the hills of North Idaho oh-so-unsustainably, Native Americans dug here for the roots of this real silver and gold. In spring, local tribes dug up smaller, carrot-sized roots, avoiding the largest taproots. Then the preparations began. First, they beat them to loosen the outer skins, then peeled, then pit-steamed overnight, then ate as is or dried and stored or powdered for flour. These roots were also boiled into medicinal teas for immunity, childbirth, headaches, and whooping cough. The roots were lit as incense in various Native American ceremonies. (Edible and Medicinal Plants of the Rockies by Linda Kershaw).

I admit to lacking root experience for two reasons: 1) I have no sense of entitlement over any field of these enough to dig them up and 2) the extensive preparations are way to "slow food" for even me, maven of the 3 hour dinner.

The new shoots, however, are much more accessible. Before AB blossoms, the newest leaf and flower stalks are good enough to eat, peeling first if you like. Tasting akin to intense celery, the Nez Perce loved their páasx (www.Native-American-Online.org) this way. Some eat the leaves as well, but the velour texture is too much of a mouthful for me, as is the name itself: Arrowleaf Balsamroot. The newest leaves can also be boiled as "greens".

The sap was used as a topical anesthetic, as well as anti: septic, bacterial, and fungal. Mashed, the leaves were placed on burns, small cuts, insect wounds and athletes foot (Edible and Medicinal Plants…) I guess moccasins weren't all they're cracked up to be.

The seeds were also a staple for Native Americans who roasted them or filled a buckskin bag and pounded them into a meal (Food Plants of the Interior). They can be used like sunflower seeds, in granola and breads.

According to Kim Williams in Eating Wild Plants, AB is ranked precisely third in importance to area tribes. This bronze medalist was bested by only Camas and Bitterroot. Clearly, a plant with all edible parts would be a top contender for favorite food, a reliable stock, and a secure investment. Silver and gold grow annually, freely, and in abundance here. As always,be 100% sure it's the AB silver/gold/green of natural-value before you bite into it.

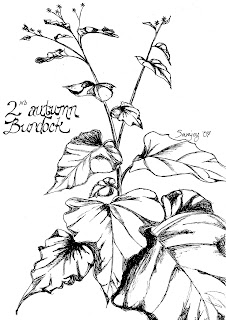

Burdock

The story begins in the dark winter when one European immigrant bur inconspicuously settles in receptive soil.

In April (Latin: Aprilis, meaning “open,” wide open), Burdock (Latin: Arctium lappa, meaning bear-seizer) lumbered awake. Without a manual or self-help book, Burdock’s root found its place in the soil and his leaves began their odyssey toward the sun. At this time, Wild-Eater noticed the unexpected visitor in her yard. She felt the thick leaves, rich with nutrition.

All summer, opulence crept into alleys, parks, creek beds and the Burdock. With abandon, Burdock offered its leaves to the sun and root to the earth. As the leaves unfurled in gratitude, the sun found a growing welcome for its energy. The cycle of gratitude and attraction fed itself. Wild-Eater inspected Burdock again. She noted his leaves, extravagant like Rhubarb’s. The layered, 1’ by 2’ (or smaller), immense heart-shaped leaves with woolly undersides were like jumbo Valentines. Thick, short stems grew from one place in the ground.

One Autumn day, Burdock said, “A good season deserves a good rest.” And with that he began to curl his sleepy leaves in.

Wild-Eater thought about using a pitch fork to dig, dig, dig up the massive white, fleshy root as intact as she could. Instead, she precisely noted Burdock’s location.

Burdock slept serenely that winter without worry. He knew his root, filled with iron, thiamine, magnesium, zinc, Vitamin A, calcium, and protein, was strong. In spring there would be energy enough to start his leaves again (Healing Wise by Susun S. Weed).

The older, wiser Burdock gracefully uncurled his leaves from a confident rosette that second spring. The Wild-Eater came again. Being 100% certain that she had identified the right plant, she took several new leaves and boiled them as greens. People have also used them in poultices: mash, dip in hot water, place leaves on burns, sores and eczema.

Wild-Eater entertained a debate about abundance vs. too much of a good thing. She foresaw the six foot tall giant with Velcro-inspiring burs dropping into her husband’s dreadlocks. Wild-Eater decided to harvest the second-year Burdock. It would die in the fall anyway, root rotting, a meal for worms and beetles only.

If Wild-Eater had been ancient Nez Perce, if her faith in the earth to provide was great as a Nez Perce’s, if she believed, as they did, that giving away remaining food stores awakened the abundance that lies in the earth, sleeping and dreaming of giving itself away, she would have given a First Roots Festival (Lecture 3/13/06 by Joy Mastroguiseppe of UI). But the Wild-Eater did not yet understand the laws of nature, abundance, gratitude, faith and attraction.

Without festival, she shoveled into her wet April yard, a wide, deep, unattractive hole. Perhaps a post-hole digger or pitchfork would be a better idea. Sweaty and tired, she finally just chopped off what exposed root there was.

Wild-Eater washed the thick root then boiled it for twenty minutes, changed the water, and boiled it for 5 more minutes, perhaps unnecessarily. She chopped and fried it with other veggies and it tasted buttery, like artichoke hearts. She might have added it to soup. She read of shredding and frying it like hash browns or roasting and grinding it like coffee. She would never feed them to pregnant ladies or diabetics.

What Wild-Eater had not foreseen that April day was her sadness the next April at finding no conveniently located Burdock. She would have to go down to the creek or borrow someone else’s Burdock now. She might collect seedy burs next autumn to plant.

If Wild-Eater now contemplates planting Burdock next year, it might just be true that you reap what you sow. Perhaps Burdock has knit himself into the fiber of Wild-Eater’s being, like a bur, and is still unleashing lessons of generosity and gratitude upon her. Perhaps he is waiting, within her, to unfurl his leaves of faith, thanksgiving and plenty, waiting for his place within her garden. Perhaps she will try First-Roots-Festival faith, and perhaps she will try gratitude for roots and burs alike.

In April (Latin: Aprilis, meaning “open,” wide open), Burdock (Latin: Arctium lappa, meaning bear-seizer) lumbered awake. Without a manual or self-help book, Burdock’s root found its place in the soil and his leaves began their odyssey toward the sun. At this time, Wild-Eater noticed the unexpected visitor in her yard. She felt the thick leaves, rich with nutrition.

All summer, opulence crept into alleys, parks, creek beds and the Burdock. With abandon, Burdock offered its leaves to the sun and root to the earth. As the leaves unfurled in gratitude, the sun found a growing welcome for its energy. The cycle of gratitude and attraction fed itself. Wild-Eater inspected Burdock again. She noted his leaves, extravagant like Rhubarb’s. The layered, 1’ by 2’ (or smaller), immense heart-shaped leaves with woolly undersides were like jumbo Valentines. Thick, short stems grew from one place in the ground.

One Autumn day, Burdock said, “A good season deserves a good rest.” And with that he began to curl his sleepy leaves in.

Wild-Eater thought about using a pitch fork to dig, dig, dig up the massive white, fleshy root as intact as she could. Instead, she precisely noted Burdock’s location.

Burdock slept serenely that winter without worry. He knew his root, filled with iron, thiamine, magnesium, zinc, Vitamin A, calcium, and protein, was strong. In spring there would be energy enough to start his leaves again (Healing Wise by Susun S. Weed).

The older, wiser Burdock gracefully uncurled his leaves from a confident rosette that second spring. The Wild-Eater came again. Being 100% certain that she had identified the right plant, she took several new leaves and boiled them as greens. People have also used them in poultices: mash, dip in hot water, place leaves on burns, sores and eczema.

Wild-Eater entertained a debate about abundance vs. too much of a good thing. She foresaw the six foot tall giant with Velcro-inspiring burs dropping into her husband’s dreadlocks. Wild-Eater decided to harvest the second-year Burdock. It would die in the fall anyway, root rotting, a meal for worms and beetles only.

If Wild-Eater had been ancient Nez Perce, if her faith in the earth to provide was great as a Nez Perce’s, if she believed, as they did, that giving away remaining food stores awakened the abundance that lies in the earth, sleeping and dreaming of giving itself away, she would have given a First Roots Festival (Lecture 3/13/06 by Joy Mastroguiseppe of UI). But the Wild-Eater did not yet understand the laws of nature, abundance, gratitude, faith and attraction.

Without festival, she shoveled into her wet April yard, a wide, deep, unattractive hole. Perhaps a post-hole digger or pitchfork would be a better idea. Sweaty and tired, she finally just chopped off what exposed root there was.

Wild-Eater washed the thick root then boiled it for twenty minutes, changed the water, and boiled it for 5 more minutes, perhaps unnecessarily. She chopped and fried it with other veggies and it tasted buttery, like artichoke hearts. She might have added it to soup. She read of shredding and frying it like hash browns or roasting and grinding it like coffee. She would never feed them to pregnant ladies or diabetics.

What Wild-Eater had not foreseen that April day was her sadness the next April at finding no conveniently located Burdock. She would have to go down to the creek or borrow someone else’s Burdock now. She might collect seedy burs next autumn to plant.

If Wild-Eater now contemplates planting Burdock next year, it might just be true that you reap what you sow. Perhaps Burdock has knit himself into the fiber of Wild-Eater’s being, like a bur, and is still unleashing lessons of generosity and gratitude upon her. Perhaps he is waiting, within her, to unfurl his leaves of faith, thanksgiving and plenty, waiting for his place within her garden. Perhaps she will try First-Roots-Festival faith, and perhaps she will try gratitude for roots and burs alike.

Ultra Violets

In the beginning was Vi(olet), an elderly nanny with a parakeet named Charlie.In her hallway hung portraits of three men.She told me they were her husbands, who had all died. I thought, "What good luck! To have three husbands! But what tragedy that they all died at once!"Years later, my parents explained to my confused self that it was only allowed for one man to marry one woman and vice versa. I protested that Vie had had 3 husbands at once. They broke to me the tragic news that her husbands had been in succession, not at once. Burst my bubble right there.

Violets are modest creatures (not ones to have three husbands at once), delicately beautiful and frustratingly ephemeral. In all their violet wisdom, they are here for a very limited time only.

Violets thrive in woodsy spots on drippy, draining hillsides.They love the shade behind a compost bin and the leaky slope beneath an apple tree. Find a trail up the south side of a hill, and as you duck beneath the trees, there is a mass of violets on the muddy hillside. They succumb to summer heat, so find them now, and sup of your little piece of ecstasy.

The violet leaf is, not surprisingly, shaped like a heart, with tiny-toothed edges.One leaf per stem, and several stems from one spot. The five-petaled, floppy "flowers" come in purple, yellow, white, cream, blue or any combination of these. Identify clean violets with 100% certainty using a reliable guide/book.

Violets are never violet. The authority on color, Roy G. Biv, asserts that violet has a shorter wavelength than blue at 420-380 nm, but is Not a combination of blue and red (that would be purple, which Is the color of many violets).

All violet flowers, including pansies and johnny-jump-ups, are edible. The so-called "African violet" is in another family all together, so don't get excited about eating your windowsill plants for breakfast.

The inscrutable, unavailable sweetness of violet flowers, which always leaves me begging for more, is explained by an ionone compound that these flowers give off along with their scent. This compound disconcertingly handicaps your sense of smell (Wikipedia.com). The deeper you inhale, the less scent you get.

Violets, the quintessential temporal tease, enforce a respect for pleasure's fleeting nature. One second you smell the faint joy of viola odorata and the next, it's gone, despite cramming the nosegay up your nose. In grasping and clinging is loss. Vi's parakeet, Charlie, taught me this too, with her eggs. Open hand: open to receive, to give, to let go. Clenched fist: for breaking stems (a necessity), noses, and little parakeet eggs during 2nd grade show-and-tell.

The flowers can be gathered without much worry about the plant's ability to propagate. These tease-scented flowers are exuberant show-offs, but the true flowers, according to Susun Weed (Healing Wise), are humble, seedy, autumn flowers.

Everyone recommends candying the show-off flowers, a laborious process involving pricey accoutrements (according to the directions I read).I would rather eat them like candy (uncandied), toss them with my dandelion-green salads, or pour boiling water over them for a purple tea.

Most information on violet edibility focuses on the flowers, but the lesser known fact about wild violets is that their leaves are an edible source of vitamin C and vitamin A. The leaves taste bland and a little sweet, perfect for adding to potent dandelion and wispy chickweed salads. Toss in some flowers and you have an extremely nutritious and beautiful salad fit for the gods. They also thicken soups.

Susun Weed recommends drinking a violet leaf infusion (pour boiling water over dried violet leaves, cover and let steep for 4 hours) for headaches, "fevered fantasies," and anxiety. Recent research confirms that violets contain, salicylic acid, a natural aspirin, "which substantiates its use for centuries as a medicinal remedy for headache, body pains and as a sedative," (altnature.com).

What violets bring to me is spiritual, sensual and edible. The scent of a heart full of love and loss. Flowers smelled, un-smelled, and devoured. Husbands loved and died. Eggs laid and crushed. Spring salads: glorious, gorgeous and unavailable tomorrow.Carpe diem, with a open hand.

Violets are modest creatures (not ones to have three husbands at once), delicately beautiful and frustratingly ephemeral. In all their violet wisdom, they are here for a very limited time only.

Violets thrive in woodsy spots on drippy, draining hillsides.They love the shade behind a compost bin and the leaky slope beneath an apple tree. Find a trail up the south side of a hill, and as you duck beneath the trees, there is a mass of violets on the muddy hillside. They succumb to summer heat, so find them now, and sup of your little piece of ecstasy.

The violet leaf is, not surprisingly, shaped like a heart, with tiny-toothed edges.One leaf per stem, and several stems from one spot. The five-petaled, floppy "flowers" come in purple, yellow, white, cream, blue or any combination of these. Identify clean violets with 100% certainty using a reliable guide/book.

Violets are never violet. The authority on color, Roy G. Biv, asserts that violet has a shorter wavelength than blue at 420-380 nm, but is Not a combination of blue and red (that would be purple, which Is the color of many violets).

All violet flowers, including pansies and johnny-jump-ups, are edible. The so-called "African violet" is in another family all together, so don't get excited about eating your windowsill plants for breakfast.

The inscrutable, unavailable sweetness of violet flowers, which always leaves me begging for more, is explained by an ionone compound that these flowers give off along with their scent. This compound disconcertingly handicaps your sense of smell (Wikipedia.com). The deeper you inhale, the less scent you get.

Violets, the quintessential temporal tease, enforce a respect for pleasure's fleeting nature. One second you smell the faint joy of viola odorata and the next, it's gone, despite cramming the nosegay up your nose. In grasping and clinging is loss. Vi's parakeet, Charlie, taught me this too, with her eggs. Open hand: open to receive, to give, to let go. Clenched fist: for breaking stems (a necessity), noses, and little parakeet eggs during 2nd grade show-and-tell.

The flowers can be gathered without much worry about the plant's ability to propagate. These tease-scented flowers are exuberant show-offs, but the true flowers, according to Susun Weed (Healing Wise), are humble, seedy, autumn flowers.

Everyone recommends candying the show-off flowers, a laborious process involving pricey accoutrements (according to the directions I read).I would rather eat them like candy (uncandied), toss them with my dandelion-green salads, or pour boiling water over them for a purple tea.

Most information on violet edibility focuses on the flowers, but the lesser known fact about wild violets is that their leaves are an edible source of vitamin C and vitamin A. The leaves taste bland and a little sweet, perfect for adding to potent dandelion and wispy chickweed salads. Toss in some flowers and you have an extremely nutritious and beautiful salad fit for the gods. They also thicken soups.

Susun Weed recommends drinking a violet leaf infusion (pour boiling water over dried violet leaves, cover and let steep for 4 hours) for headaches, "fevered fantasies," and anxiety. Recent research confirms that violets contain, salicylic acid, a natural aspirin, "which substantiates its use for centuries as a medicinal remedy for headache, body pains and as a sedative," (altnature.com).

What violets bring to me is spiritual, sensual and edible. The scent of a heart full of love and loss. Flowers smelled, un-smelled, and devoured. Husbands loved and died. Eggs laid and crushed. Spring salads: glorious, gorgeous and unavailable tomorrow.Carpe diem, with a open hand.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)